An important part of an archaeologist’s job is the wearisome process of categorizing shards of pottery into subtypes.

‘It’s kind of like looking at a photograph of Elvis Presley and looking at a photo of an impersonator,’ said Christian Downum, Anthropology Professor at Northern Arizona University. ‘You know something is off with the impersonator, but it’s hard to specify why it’s not Elvis.’

Now, archaeologists have demonstrated that a computer could be programmed to this crucial part of their job as well as they can. In a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, researchers reported that a deep-learning model classified images of decorated shards as accurately and even more precisely than four expert archaeologists.

‘It doesn’t hurt my feelings,’ Dr. Downum, a co-author of the study. Instead, he said it should improve the field by freeing up time and replacing ‘the subjective and difficult-to-describe process of classification with a system that gives the same result every time.’

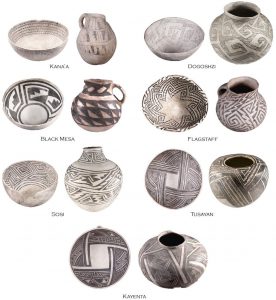

The study emphasized on Tusayan White Ware, a kind of painted hand-formed pottery used for serving food and storing water in the canyons and mesas of Northeastern Arizona between 825 and 1300. In the 1920s, archaeologists discovered that Tusayan White Ware pieces have consistent patterns depending on the time period they were created.

Four of the most experienced analysts of this kind of pottery were recruited by the researchers. They spent about four hours training a neural network to sort photographs of Tusayan White Ware.

Human and machine were tasked with classifying thousands of images into one of nine known types and examined on the accuracy of their answers.

The researchers found that the neural network beat two of the human analysts and tied the other two for accuracy.

The machine was also more efficient. Because the task was monotonous, the human analysts didn’t want to go through all 3,000 photographs without stopping, said Dr. Pawlowicz. Although they could have finished the task in three hours, each conducted the analysis through several sessions over three to four months.

The neural network on the other hand, completed the task in a few minutes.

The computer program was also able to better articulate why it had classified the shards in a certain way compared to its human competitors. In one case, the computer offered up a smart sorting observation new to the researchers: It pointed out that two similar types of pottery with barbed line design elements could be distinguished by whether the lines connected at right angles or were parallel, said Leszek Pawlowicz, another co-author.

The machine also did better than the humans in offering only one answer for each classification. The archaeologists often conflicted on how items were categorized, which often slows down archaeological projects.

Phillip Isola, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Professor at M.I.T, who wasn’t involved in the study, stated he was not surprised that the neural network performed better than archaeologists.

‘It’s the same story we’ve heard a few times now,’ said Dr. Isola. In the field of medical imaging, research has found that neural networks compete squarely with radiologists at identifying tumors. Academics also use similar tools to categorize plant and bird types.

This is not the first time that archaeologists have turned to artificial intelligence. In 2015, French researchers applied machine learning to the classification of medieval French ceramics. A team of archaeologists and computer scientists from five countries are also developing a digital tool to categorize pottery shards.

Since the study went public, some archaeologists shared concerns that they could be replaced by machines in their jobs. Dr. Downum and Dr. Pawlowicz stated they weren’t concerned about such a thing happening.

‘We’re the ones that decide what’s important to study,’ said Dr. Downum.

By Marvellous Iwendi.

Source: The New York Times